The Columbian has explored the history of the Interstate 5 Bridge — from the first ferry service in 1846 to the opening of the second span — in a series of stories over the past year.

Our research turned up interesting historical tidbits that we couldn’t fit into those accounts — border dust-ups, toll scofflaws and bridge-lift brouhahas — so we’re sharing them here.

Enlarge

The Columbian files

Bi-state struggles

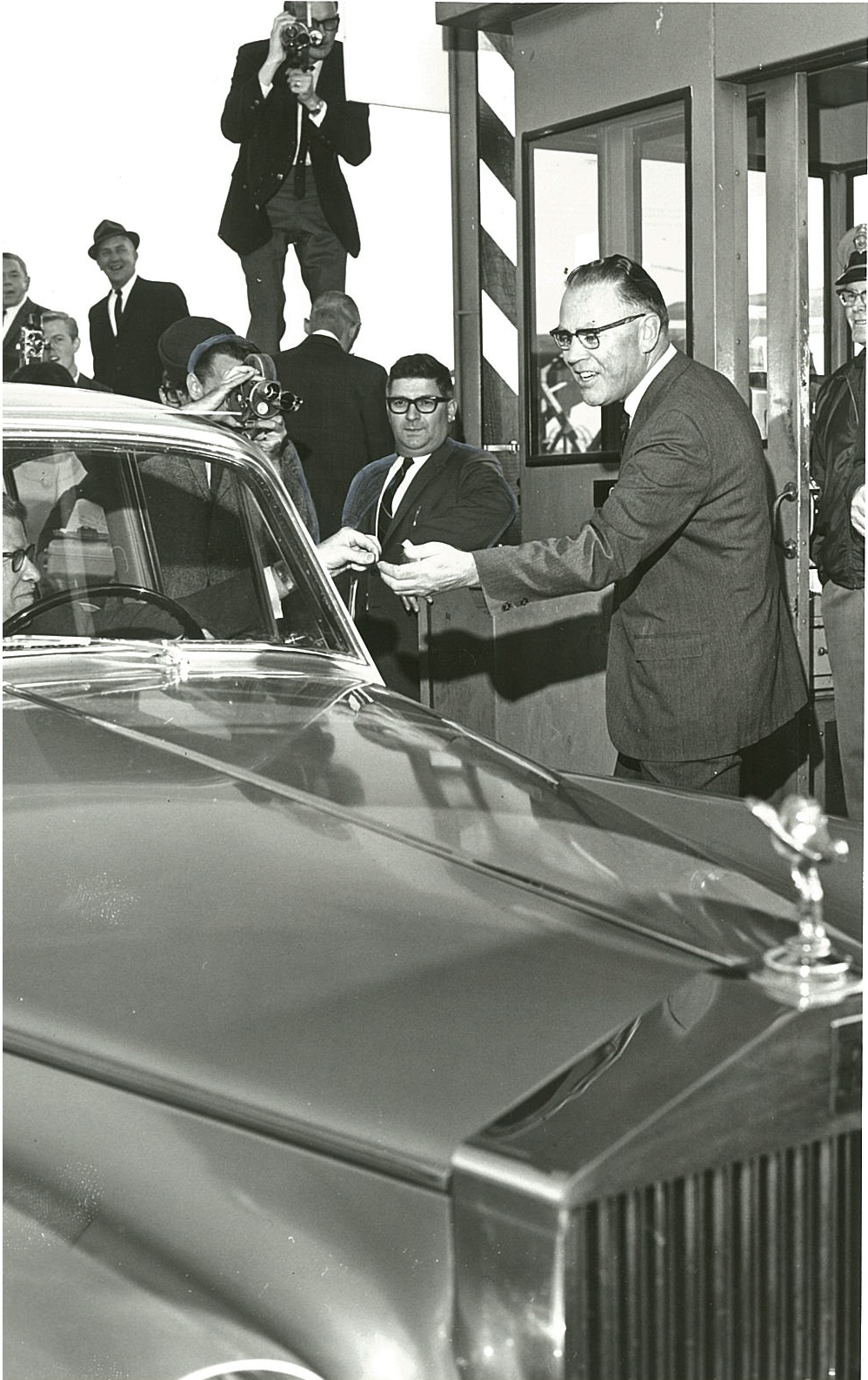

It was a frigid Christmas Eve in 1963 when the workers on the Interstate 5 Bridge received what The Columbian called “a loaded hand grenade” for Christmas. Well, a figurative one at least.

The “grenade” was a letter from the state of Oregon notifying the toll collectors that they needed to pay back taxes from 1960-63.

None of the 38 employees lived in Oregon. None of them worked for an Oregon employer, either. They worked for the Washington Toll Bridge Authority. The issue was that the toll booths where they reported to work were on Hayden Island in Oregon. In all, the workers owed $14,000, about $140,000 today.

The tax problem was overlooked by the two states when they agreed to build the second Interstate Bridge span, said Washington Attorney General John O’Connell.

The confusion didn’t stop there. Before Congress passed the Uniform Time Act in 1966, clocks in Washington did not fall back and spring forward. Clocks in Oregon did, however.

But the exact line between the two states was fuzzy. The toll collectors worked in Oregon but were employed by Washington and the bridge operators were employed by Oregon and worked primarily just feet off the Washington shore. Eventually, it was decided that toll bridge operators would go on daylight saving time, but clocks above the toll plaza would remain on standard time.

Enlarge

The Columbian files

Toll cheats

A 1963 audit found that 300 toll evaders crossed the bridge a day, resulting in $60 in lost income, about $600 today. The toll cheats used an assortment of items to dupe the system: flattened pennies, foreign coins (some worth more than the cost of a token), merchandise slugs, washers and pieces of linoleum cut to size. In some cases, drivers inserted candy wafers that jammed the equipment so it would continue to register paid tolls for nonexistent vehicles.

The assumption was that the toll cheats were Washington residents who worked in Oregon, as most of the counterfeit was found on the southbound span in the morning and the northbound span at night.

Given that the toll facilities were on Hayden Island, Oregon State Police occasionally cracked down on toll offenders and arrested motorists who failed to pay. Caught offenders typically paid $15 to $20 — roughly $150 to $200 today — much more than the 20-cent toll.

After the states removed tolls from the bridge in 1967, the Washington General Administration Department auctioned off the accumulated junk tossed in the hoppers. The amount earned was never reported.

Enlarge

The Columbian files

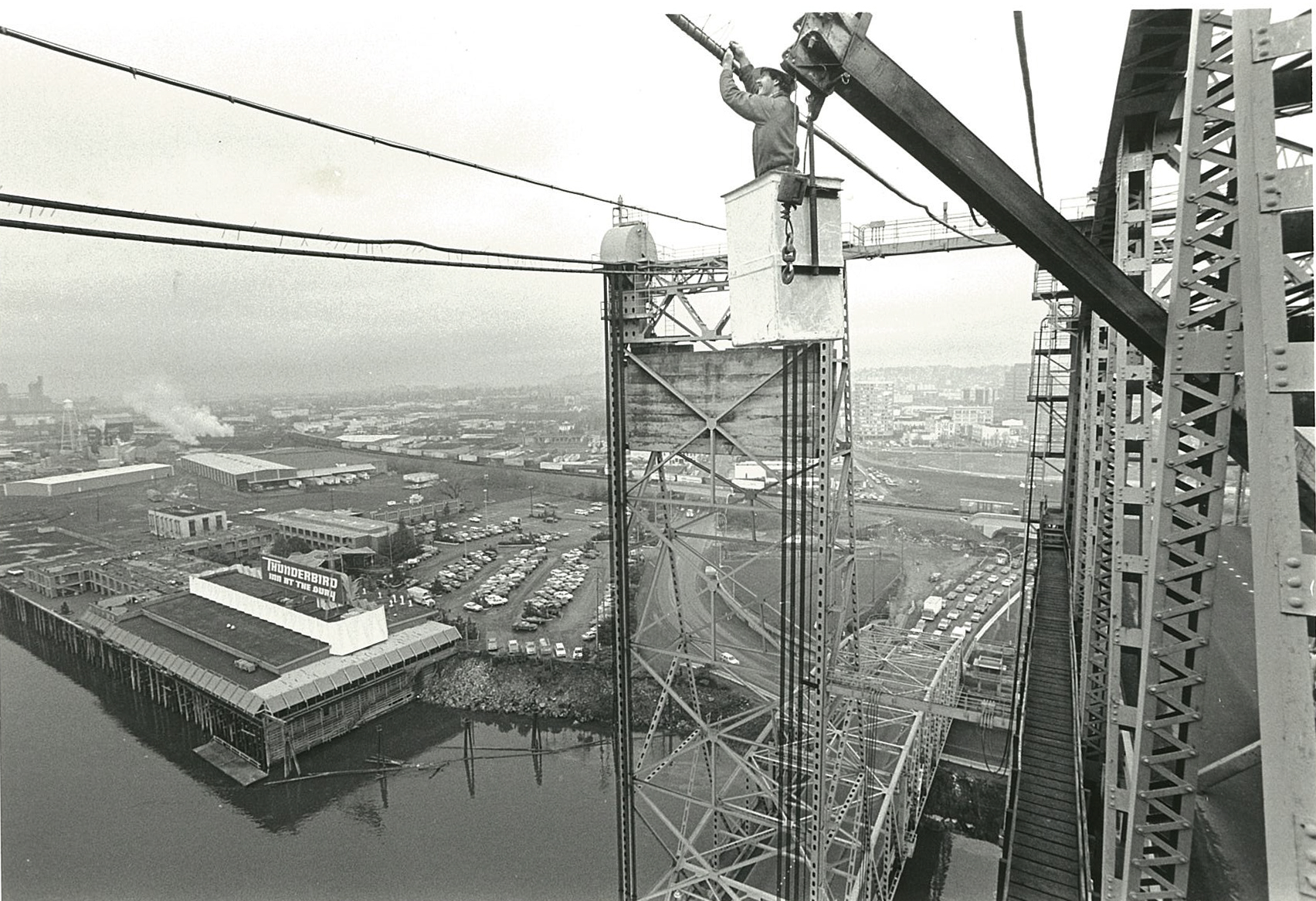

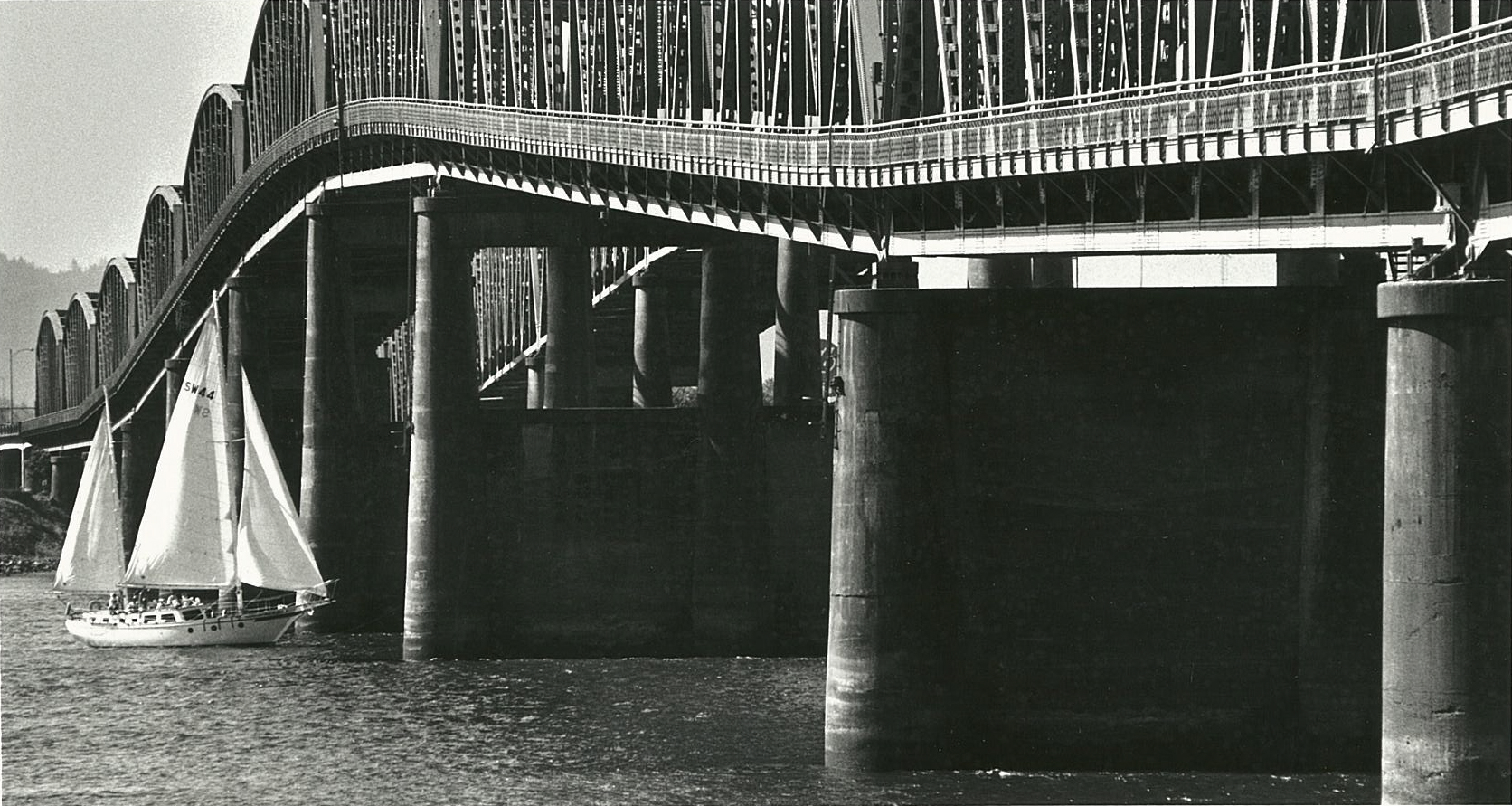

‘Thanks tugboaters’

“That *&X*%& draw bridge,” a Columbian editorial exclaimed in 1972. Congestion over the bridge had increased significantly. The average weekday crossing numbers had doubled since 1962, and the Interstate 205 Bridge wouldn’t be built for another decade.

“Even if there is no particular crisis, the mere volume of traffic is enough in itself to cause slow-down and near standstills,” the editorial stated. “A flat tire or empty gas tank on the bridge, not to mention collisions or other accidents, can take hours to clear.”

In 1959 the bridge opened for river traffic 4,255 times, 710 of which occurred during rush hour traffic. Today the Interstate 5 Bridge lifts about 260 times per year. About 150 of the annual lifts are caused by vessels, with the rest caused for maintenance.

But what frustrated drivers the most was that boaters could request the bridge to be lifted at any hour of the day. Vancouver, the Port of Vancouver and boat operators had discussed regulating bridge lifts during rush hour in the late ’60s, but nothing developed until 1973 when river tugboaters voluntarily agreed not to request bridge openings between 6:45 to 8:15 a.m. and 4:30 to 6 p.m.

Enlarge

The Columbian files